News

Gulf Hagas, a Painting by Joel Babb is Aquired by the

Portland Museum of Art

The Portland Museum of Art has accepted a painting by Joel Babb for the collection as a gift by an anonymous donor in honor of Walter Goldfarb. The painting is expected to be hung in the galleries later this spring. Gulf Hagas is a gorge in the northern Maine woods in the mountains of the hundred mile wilderness portion of the Appalacian Trail. The West Branch of the Pleasant River makes a canyon of three miles length with a series of beautiful waterfalls. The painting is expected to be hung in the galleries later this spring. Walter Goldfarb was a Portland Surgeon who has given much of his own collection of 19th Century American paintings to the PMA.

Copley Plunge to Boston Museum of Fine Arts

The acquisitions subcommittee of the board of trustees of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has accepted the gift of the painting Copley Plunge this October, 2017. The painting was given to the museum by a collector in Maine.

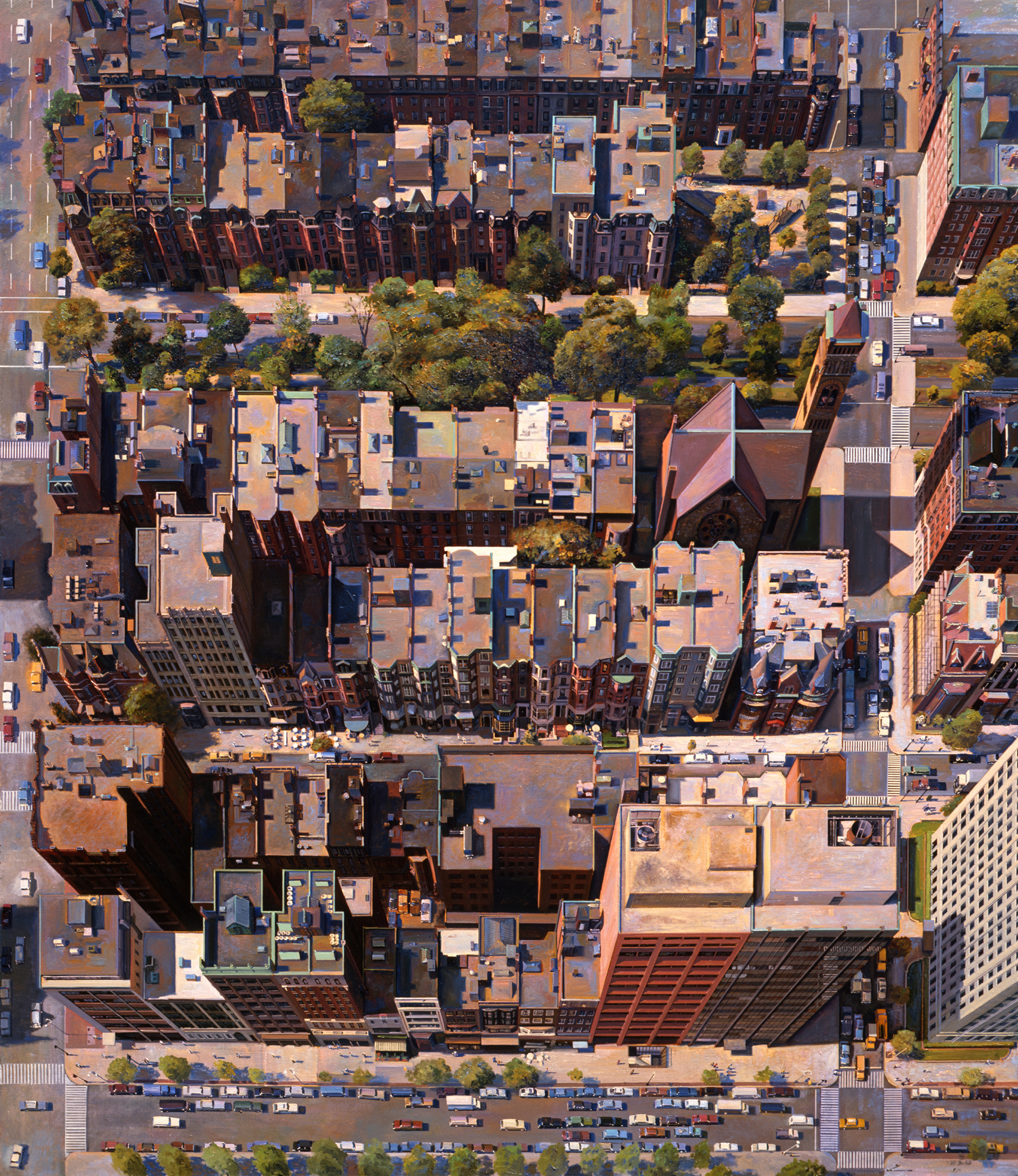

Copley Plunge, 1990, oil on linen, 82 x 65 inches, Museum of Fine Arts Boston

The Space of Copley Plunge

Copley Plunge dates from a period in which I was experimenting with various perspectives. There is the perspective invented by Brunelleschi and Alberti—with many refinements elaborated in the Baroque used in painting illusionistic ceilings in churches and palaces. Andrea Pozzo’s treatise on perspective described the methods he used in painting his tour de force in S. Ignazio in Rome. My time in Rome gave me an interest in these methods of integrating architecture and illusionistic painting.

There are different perspective systems used in Chinese and Japanese cityscapes—being axonometric, or peculiarly isometric they are yet capable of describing spaces which one may move in all dimensions, but imbuing the space with a strange feel to eyes accustomed to Western perspective. We know we don’t get smaller moving down a street—yet in Western perspective things become tiny as they move far away, whereas in Eastern space they remain the same size. Both systems have their logic in dealing with space.

In the 1980’s I took many photos from a small helicopter with the door removed, flying over Boston, to do paintings which render familiar places in an unfamiliar perspective. Kirk Varnedoe explored the transformative perspective of aerial views in his book, A Fine Disregard: What Makes Modern Art Modern. He discusses E. A. Abbott’s Flatland, a two dimensional world in which a three dimensional world cannot be imagined, until the two dimensional narrator is taken for a flight above his world and has a perspective on the perspectives of Flatland. Our experience of the city is usually navigating on a flat plane—but the aerial view offers another perspective on those earth bound perspectives.

Varnedoe also mentions a painting by Caillebotte of a street seen from a window above with foreshortened figure and tree, and he quotes a writer who quips “M. Caillebotte has created a painting which is meant to be exhibited on the floor.”

Copley Plunge is just such a painting. It is a one point perspective from a high building, such that the verticals of buildings meet at a vanishing point below the viewer’s feet. This is the same one point perspective which Durer invariably used in his prints, but rotated downward so that the vanishing point is straight down instead of at a point on the horizon.

A peculiarity of this is that the streets run up and down the sides of the picture, instead of converging toward a vanishing point on the horizon, and houses and cars don’t get smaller as they get farther away near the top of the painting, but they stay the same size. So even though the perspective is correct and consistent it isn’t what eye or the camera sees. However, if the painting is laid on the floor, and the viewer looks with one eye while standing one foot below the bottom edge of the painting, the scene is reconstituted: The sides of the painting itself converge to a vanishing point on the horizon, and the perspective of the streets on the sides converge to a vanishing point on the horizon. The buildings seem to pop up perpendicular to the ground instead of being elongated outward as they do when the painting is hung on the wall.

In painting the picture I attached a board to the bottom edge of the picture and placed a long nail at the vanishing point for the verticals one foot below the bottom edge. A long stick with a notch at the bottom which fit over the nail served to determine the angles of the verticals when drawing and painting the buildings. This was all worked out in preliminary drawings.

The title Copley Plunge comes from the unusual feel of the space when the picture is seen hanging on the wall, thus viewed from an incorrect point of view, not perpendicular to the vanishing point, suggesting a space which draws one not into the distance, but toward the center of the earth.

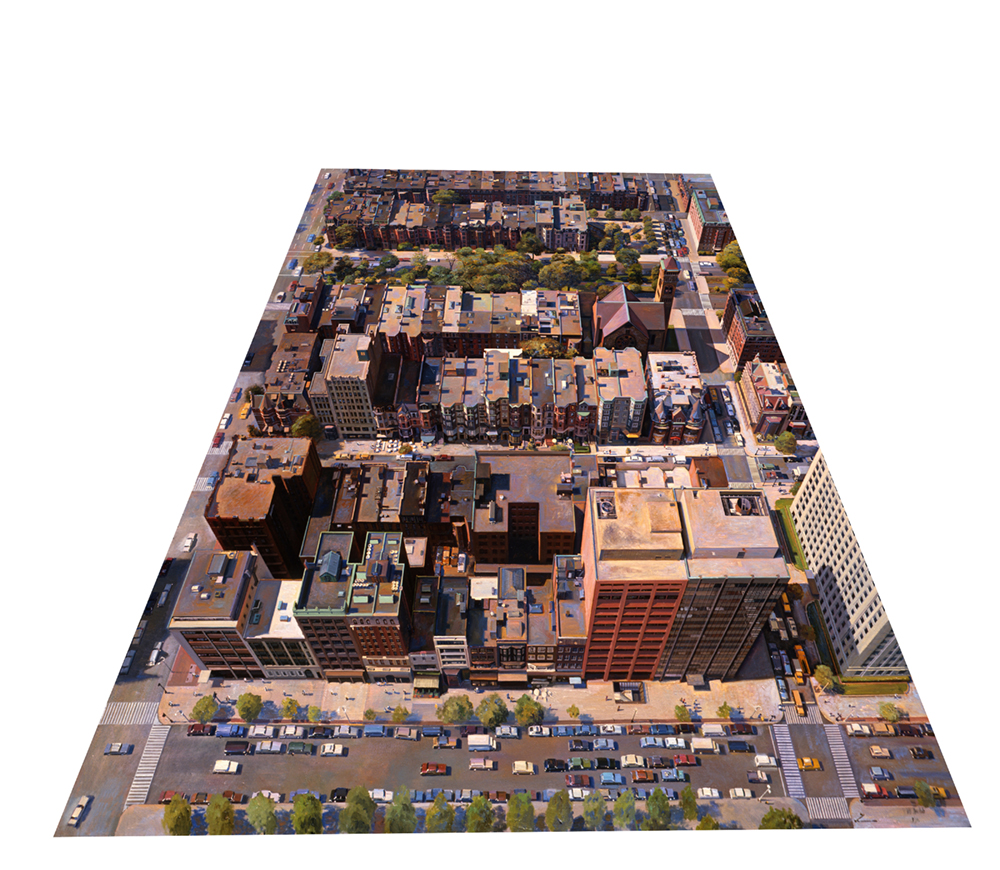

Copley Plunge as it appears exhibited on the floor, viewed from above the vanishing point.

The Bowdoin Orient–October 12, 2018

Landscape painter Joel Babb explores his Renaissance

OLD IS NEW Maine-based painter Joel Babb finds inspirations in the cityscapes of Boston and captures fleeting sensations in nature. Citing influences from Leonardo, Canaletto and Lorrain, Babb is the modern Renaissance man.

On October 3, Joel Babb, a renowned landscape painter based in Sumner, Maine, presented his art and creative process in the Edwards Center for Art and Dance. Referencing Roman monuments and Baroque landscapes, he guided his audience through his decades-long journey in capturing nature and culture.

As an undergraduate art history student at Princeton in the late 1960s, Babb painted in an abstract manner, producing Surrealist expressions of imaginative fantasies in line with popular tastes at the time. During a seven-month stay in Rome after graduation, Babb began attempting to sketch and paint his surroundings, grappling with representing the world as he saw it.

His stylistic switch from abstraction to realism was inspired by his discovery of Old Master works, a passion that took form while he worked as a night watchman at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and enrolled in the Museum School. Navigating his own artistic endeavors, Babb found guidance in the work of Leonardo da Vinci and became fixated on his anatomical sketches. In this early stage of his artistry, he practiced a little bit of everything.

“I had a Renaissance of discovering all the things that Renaissance artists [learned],” Babb said. “I began that same process too, in terms of drawing from Roman architecture and drawing from Roman statues … it’s occurred to me lately that every artist who sets out on his process of becoming an artist should have this period in the Renaissance, trying to rediscover what was in the past, and what was to some extent lost.”

Babb found his calling in the landscape paintings of the greats.

“I really had no ability to capture a landscape in drawing or painting until I discovered Claude [Lorraine’s] drawings,” he said, citing the 17th century French painter as a major influence.

Babb’s world, however, looked vastly different from the Italian ports Lorraine favored. Boston, his city of residence, lacked the wide open skies and mossy ruins of Rome—yet he saw an opportunity for creation. Boston would be his muse.

One particularly breathtaking example of his cityscapes is “Copley Square from 500 Boylston.” Its canvas is filled half with the reflective windows of the John Hancock building, a mirror of the city around it.

To create this piece, Babb spent a lot of time taking 4×5 inch photographs from the roof of 500 Boylston Street in Boston. The work takes on a previously unseen level of detail that he says was inspired by two shows he had seen before doing the painting. The first was an exhibition of the Baroque painter Canaletto, whose epic landscapes depicted both city and country. The second was an exhibition of Richard Estes paintings, a painter whose New York street scenes are almost indistinguishable from photos. Babb used both artists’ techniques of capturing light and defining depth and perspective to create a modern tribute to landscape artists of the past.

Eventually, Babb found the cityscapes and their endless detail exhausting and moved to Maine for a change of scenery. He had been granted some land by a friend and built a studio and home in Sumner. There, his landscapes turned from the brick and cement of Boston to the woods and streams of rural Maine.