Press & Books

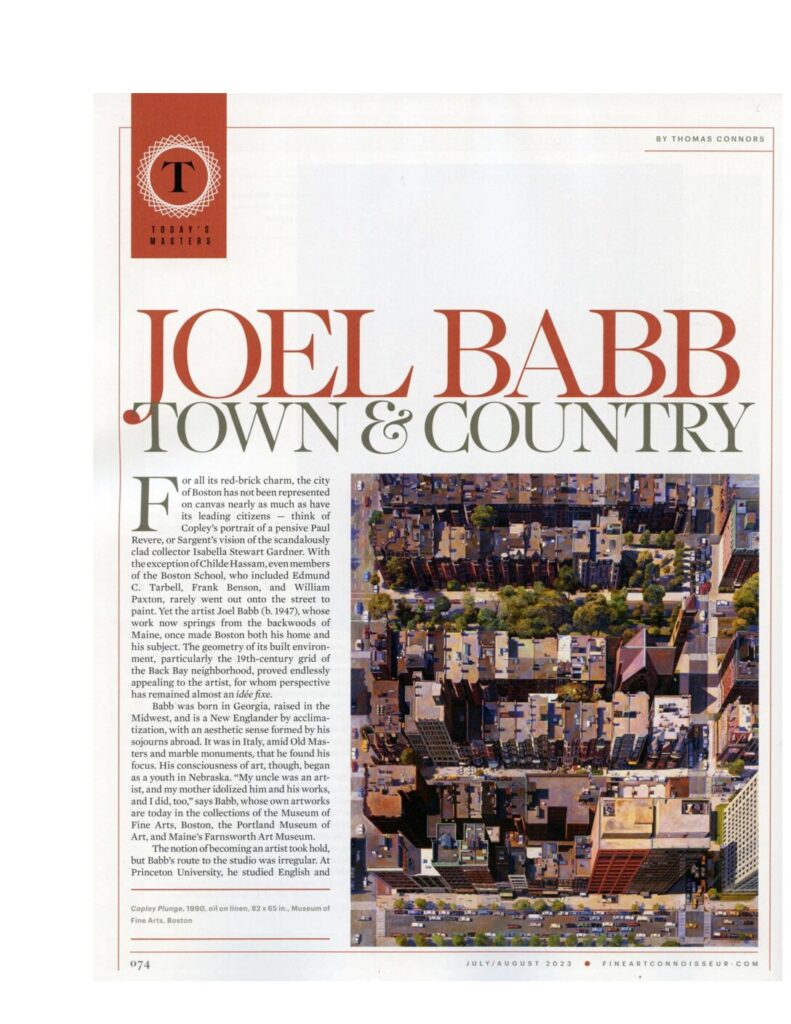

Fine Art Connoisseur by Thomas Connors

Nature and Culture: The Art of Joel BabbCarl Little (Author), Christopher Crosman (Contributor), Bernd Heinrich (Contributor), Anita Shreve (Contributor)

download Enlightened Perspectives catalog

Portland Press Herald Maine Sunday Telegram September 9, 2018

Posted 4:00 AM

Meet Joel Babb, the painter of Boston who lives deep in the woods of Maine

The Museum of Fine Arts recently acquired one of his cityscapes.

BY BOB KEYES STAFF WRITER

SUMNER, ME – AUGUST 24: Artist Joel Babb poses for a photo in his studio in Sumner on Friday, August 24, 2018. (Staff photo by Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer)

SUMNER — It was on the streets of Rome where Joel Babb became a painter, and it was above the streets of Boston where he became a master. But it was deep in the Maine woods, where he’s been coming since 1971 for solitude, light and air, that Babb became a Renaissance man.

A modern master of vision and technique, Babb combines the traditions of European masters with his own contemporary sensibilities to create large-scale, near photo-realistic oil paintings of complex cityscapes, the tangled woods of his western Maine home and the austere Down East coast.

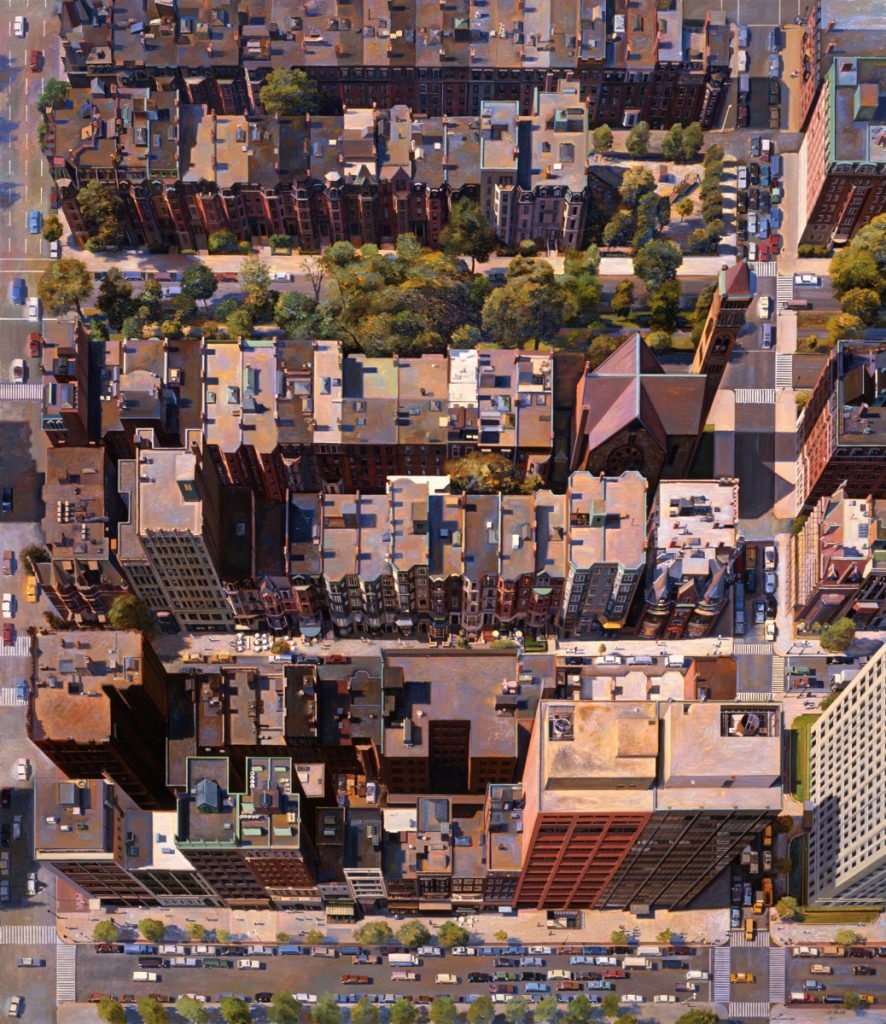

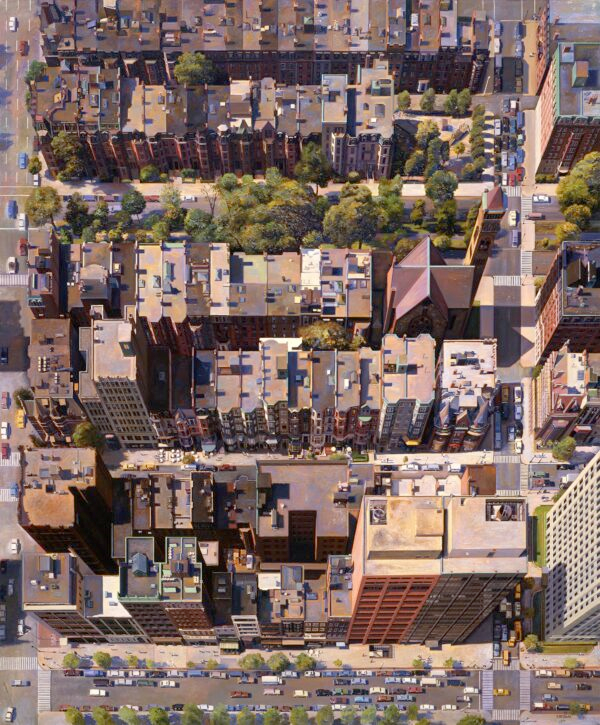

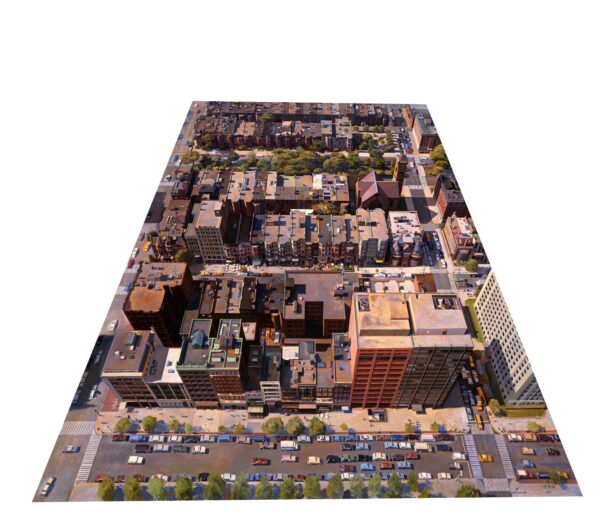

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston recently acquired one of his cityscapes, “Copley Plunge,” which Babb painted in exacting detail from the perspective of the top of New England’s tallest building, the former John Hancock Tower in Copley Square, looking directly down over the Back Bay, showing the rooftops, treetops and the car-cluttered streets from a birds-eye perspective. The museum’s acquisition of “Copley Plunge” completed something of an artistic circle for Babb, who came to Boston in the early 1970s when he enrolled in the master’s program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. “The museum helped build me into the artist I am,” he said.

Copley Plunge” was recently acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Photos courtesy of Joel Babb

Placing the painting in the MFA’s collection – it was offered as a gift of a collector and accepted by a committee of curators – is both gratifying and rewarding, he said, a highlight of his career.

In the near 50 years since his grad school days, he’s become the contemporary painter of Boston, occupying the hallowed ground of John Singleton Copley, Childe Hassam and Winslow Homer as artists whose work is closely identified with the city. His paintings anchor public and private collections in university libraries, hotels, hospitals and the board rooms of banks and law firms across Boston, Cambridge and beyond.

Longtime curator Wes LaFountain compared Babb to the great European landscape painters of old. “For all his beautiful wooded landscapes and rocky seascapes, Joel Babb is to Boston what Canaletto was to Venice,” said LaFountain, who met Babb when LaFountain directed the former New O’Farrell Gallery in Brunswick. He organized an exhibition about Mount Katahdin and included a sketchbook of Babb’s that documented a series of climbs.

“I learned what a great craftsman he is,” said LaFountain, who is now the interim director and curator of the Lamont Gallery at Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire.

Babb cites the French painter Camille Corot as a key influence. Beginning the summer after college, Babb has made a habit of going to Rome for extended stays and painting scenes that Corot painted, following in the artist’s footsteps to see what he saw and to learn how he did it.

After taking a break from the cityscapes that established his reputation in the 1980s, Babb has recently returned to them with renewed vigor and interest. His new cityscapes feel less contemporary and more traditional than the earlier ones, including “Copley Plunge,” which he painted in 1990.

They’re still of photo-realistic quality, but one senses the influence of the Raphaelists and the Hudson River School of painters in Babb’s new canvases. They evoke reverence for a higher wonder. Amid the ordered chaos of a high-rise landscape, the artist expresses an awe of nature and weather and the complexity of the natural world. His newer paintings of the city are layered with atmosphere and feel almost three-dimensional. He wants people to feel that they are looking not at paint, but through space.

Babb works on a Boston cityscape in his Sumner studio. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

MAKING OF A MASTER

Babb, 71, is a product of his time and place, and his path to art was not something he necessarily chose as much as an instinct he followed. He was born in Georgia in 1947. His father worked for the federal government as an agricultural engineer, and the family moved often, mostly around the Midwest. Babb graduated from high school in Lincoln, Nebraska, a place he most identified as home but has not been back to visit since he left for college in 1965.

His exposure to art came from visits to the Sheldon Museum on the campus of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln – now directed by Wally Mason, who formerly directed the University of Maine Museum of Art in Bangor. It was at the Sheldon where Babb saw his first Andrew Wyeth painting, a watercolor of a tree stump and roots from 1943 called “Spring Beauty.” Babb liked the feeling of being out in the woods that the painting inspired, and that sense of being in a specific place, among nature or on a city sidewalk, is something he’s tried to achieve in all his work.

He came east to Princeton University, an earnest kid from the Midwest with a sense of adventure. “Everybody there is so damn smart, and they’re all good at something,” he said. “At Princeton, you’ve got play to your strong suit, and art was mine. Art became my identity before I realized what I had to do to become an artist.”

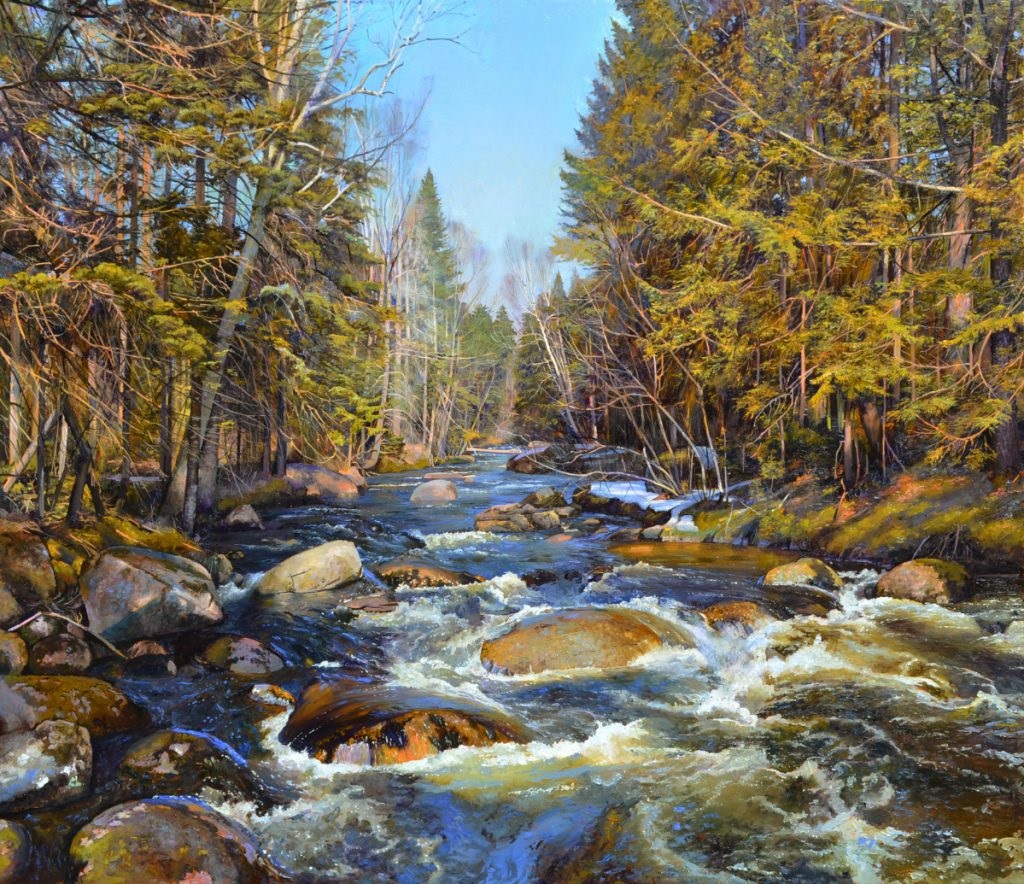

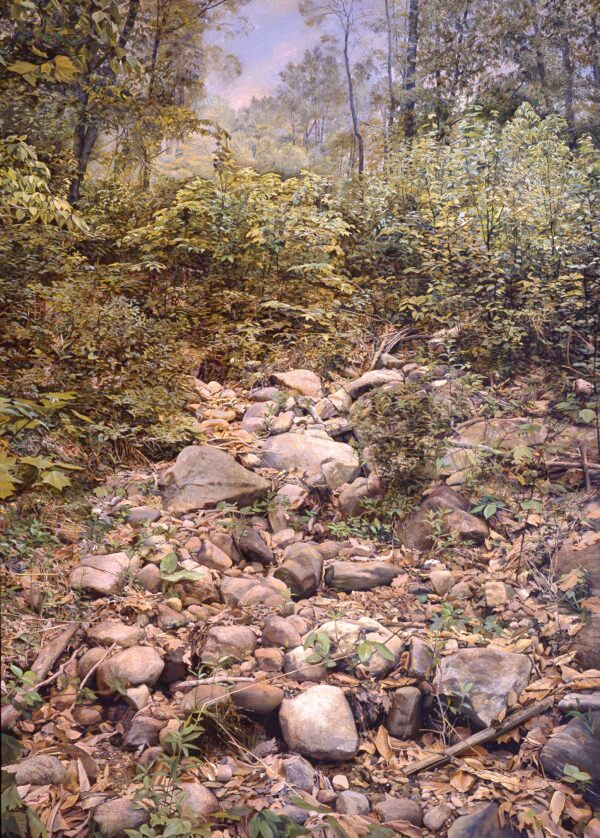

“Bernd Heinrich’s Brook,” 40 by 52 inches. “Nature is relatively untended in the Maine woods,” Babb wrote.

He figured it out quickly, by the sheer will of survival. After graduating, he went to Europe to work first as an intern at the Bavarian National Museum and then to live on his own in Italy, where he studied directly from the work of European masters. He spent seven months there, mostly in Rome, drawing the city and immersing himself in its history of architecture, sculpture and art. Before the money ran out and he had to go home, he learned to be frugal and industrious and to take advantage of the circumstances.

“I got to Italy, and I got stuck there – and it gave me a shot at being an artist,” he said.

The next lesson came soon after he returned to the states and enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. To make ends meet, he reluctantly took a job as a night watchman in the museum’s galleries. He wanted to be an artist, not a gallery guard, and the necessity of work was a hard but valuable reality to accept. “It was demoralizing and depressing, the whole scene. But it was perfect. It turned out to be fabulous,” he said.

Being a night watchman gave him unfettered access to the galleries, and Babb, who recognized his shortcomings as an artist, used his time to sketch and sketch and sketch, just as he did in Rome. He studied the art on the walls, practiced techniques and absorbed everything he encountered. “Every patrol, I would stop and find a painting and do a drawing,” he said. “I still have a pile of sketchbooks from then.”

He came to Maine for the first time in 1971, at the invitation of a friend. A few years later, that friend gave him an acre of land in Sumner, understanding what such a gift could mean to an emerging artist of modest means. Babb began building his studio in 1975 and moved here permanently with his wife, Frannie, in 1988.

When he arrived in Sumner, he sat for long periods of time on his land, making pen and ink drawings of plants in the field. It was his way of getting to know the place at the root level. Later, when he decided to pursue paintings of medical surgeries, he bought a human skeleton, which he still owns, to study anatomy. He felt like Leonardo da Vinci, whose interest in botany, anatomy and the sciences formed the foundation of his art.

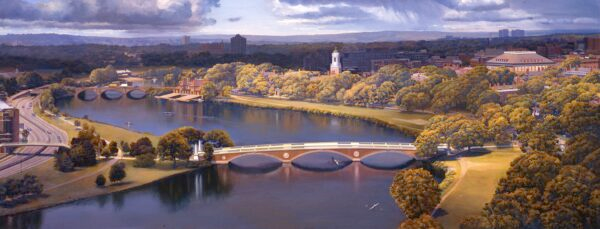

Babb’s career ascended in 1984, when he landed two commissions for large paintings. One was for the lobby of the Charles Hotel in Cambridge, a panoramic view that became “Harvard Square Panorama,” a painting that’s 5 feet high and 20 feet long. The other was another 20-foot painting for Cambridge Savings Bank at Harvard Square.

The paintings did at least three things for Babb. They established him in Boston as a painter and put his work in front of curators and collectors. They forced him to experiment with and conquer the technique of creating perspective, leading to dramatic transformations in his art. In addition to seeking out Boston’s best views from tall buildings, Babb hired a helicopter pilot to fly him over the city with the doors of the small craft removed, so he could take better source photos for his paintings.

Equally important, the commissions also led him to fully entrench in his studio practice in Maine. For the Charles Hotel painting, he encamped to Sumner with a seven-week deadline, painting through the early winter in his uninsulated studio. Four years later, in 1988, the Museum of Fine Arts built a workshop on its Boston campus to accommodate a visiting artist. When the artist finished his work, the museum auctioned the workshop. Babb won it and moved it to Maine, and that year, he and his wife moved here full-time. They lived simply and frugally, with Babb traveling to Boston to teach. He gave up teaching in 2003 and has been painting full-time since. They expanded their home and studio in 2009.

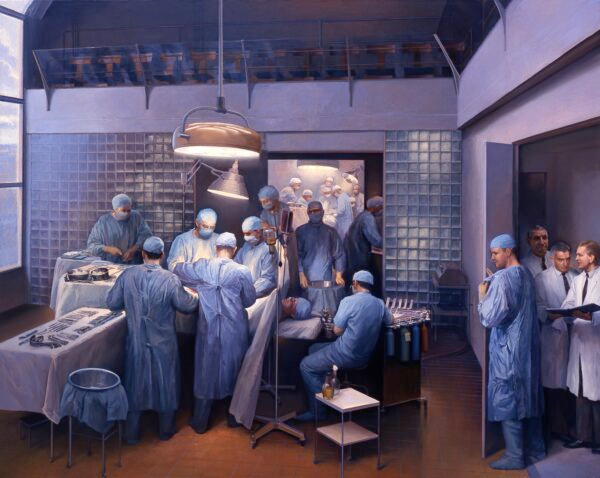

In the 1990s, Joel Babb took a commission to recreate on canvas the first organ transplant in a human, a kidney operation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston in 1954.

NATURE AND SCIENCE

His studio today is large and airy, filled with paintings on the wall and on the easels, some finished, others just under way. There are art books everywhere, and classical music plays softly.

Maine also gave him something to paint. He finds as much challenge and reward making large-scale paintings of the deep Maine woods as he does painting the city. But they are very different experiences as an artist.

He writes of his Maine experience, “Nature is relatively untended in the Maine woods, and one soon becomes entangled in anarchic competition of self-organized processes of growth and succession in the forest. Linear perspective, which order the recession of city streets, seems nowhere in evidence in the woods. And there is hardly any atmospheric perspective to express distance and recession as in a Claude Lorrain painting – in fact there are so many trees there is hardly even a view.”

In the mid-1990s, Babb accepted a commission from a trio of doctors who participated in the first organ transplant in a human, a kidney transplant at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston in 1954. The subject of surgery was of personal interest. Babb underwent a heart operation when he was 13, and it created trauma in his life. The painting helped him process his feelings surrounding that event. It also presented an artistic challenge of another sort. This would be a historical painting based on interviews with participants and a handful of existing photos. Babb wanted it to be exactly right, down to the pattern of light as it passed through a glass brick wall in the surgical suite.

Babb used one of the historical photos to get started and worked through several stages of the composition. The doctors gave him sketches, and one of the original surgeons laid out all the instruments in an operating room at the hospital so Babb could photograph them.

His painting depicts the morning of the operation just before Christmas, with the team scrubbed and gowned as the doctors prepare to receive the kidney from a donor. “It was a great experience in giving insight into the way artists of the past created history paintings, gathering information from many sources to make some past event come to life before your eyes,” Babb said.

“The First Successful Organ Transplantation in Man” hangs in the Countway Library at Harvard Medical School, opposite Robert Hinkley’s “First Operation Under Ether.” The two paintings are seen as landmark artworks, expertly and accurately representing important moments in medical history.

“They took down a John Singleton Copley to put this painting up,” Babb said with a measure of pride. “It was and still is a wonderful adventure. I wanted to do a history painting, and I was thinking of Rembrandt and Eakins.”

Babb wasn’t done with his medical pursuits. He arranged to witness and photograph a coronary bypass operation, which he turned into another epic painting that documents a modern surgery with a room full of equipment and machines. This one remains in his private collection.

Babb is as busy as ever. He is working on new paintings for his next Portland exhibition in 2019, at Greenhut Galleries. He also shows regularly at Vose Galleries in Boston. He and Frannie recently spent a short vacation at Biddeford Pool, and several paintings that he started there may end up in an upcoming show. His easels are filled with paintings from Boston and Maine in various stages of completion.

One thing he knows is that his paintings are timeless. In art, fashions come and go. What’s hot today we may forget in a decade. Babb’s paintings will survive, because the art of masters always does.

Following Leonardo: American Artist Joel Babb on Becoming a Successful Realist Painter

June 17, 2021 Updated: June 17, 2021

Maine-based realist painter Joel Babb very nearly became an abstract expressionist. But a series of events compelled him to follow past masters—Leonardo da Vinci, Claude Lorrain, and John Ruskin, to name a few—to become the successful artist he is today.

Babb’s work is featured in private collections and in prominent ones, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and Harvard Medical School

His paintings include architecture of ancient and Renaissance Italy, cityscapes of Boston, and woodlands, especially those near his home and studio in Sumner, Maine.

“The Weeks Bridge, Charles River, Cambridge,” 1998, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 37 inches by 97 inches. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

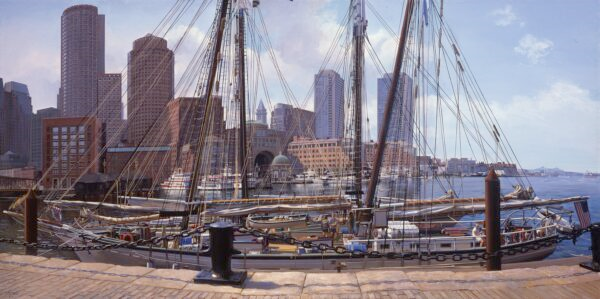

“The Fan Pier, Boston,” 2007, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 24 inches by 48 inches. Collection of Abbot W. and Marcia L. Vose. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

A Modern Beginning

In high school, Babb immediately responded to abstract expressionist painting. At the time, he believed that the growing popularity of modern art was part of a long process of modernization when things were becoming better. Princeton had a very strong program in Chinese painting, so besides learning Western art history, Babb was introduced to Chinese art too. “It’s a wonderful tradition of which I knew nothing about at the time,” Babb said in a telephone interview. He was taught by the late Wen Fong, who went on to become a curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Babb recalls a 1969 exhibition called “In Pursuit of Antiquity: Chinese Paintings of the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Earl Morse.” He learned that Chinese painters looked to the past, to the Northern Song or earlier traditions, emulating the earlier style as an expressive mode.

“What fascinated me was that an artist could paint in the style of various early masters, not just imitating one. There was a reverence and deep understanding of the past. This was so different from the obsession with innovation and originality in modern Western art,” he said.

Babb found something similar when he spent seven months in Italy, on what he says was the start of his personal “pursuit of antiquity.” In Rome, he noted that “artists who were painting in the late 15th century were really pursuing an enterprise very similar to that [of the Chinese artists] in terms of trying to re-create what the Greco-Roman tradition had been doing.”

“On the Via Giulia, Santa Maria dell’ Orazione e Morte,” 2008, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 20 inches by 28 inches. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

He was fascinated by how the different eras—the Renaissance and Baroque, for example—rediscovered and reinterpreted classical antiquity in art and architecture.

“So the sort of a simplistic idea of modernism superseding and being better than everything that had come before it just was not all that interesting [to me] anymore,” he said. He realized that all the early modernist movements, like dadaism and so forth, which had so fascinated him, were disruptive to the whole cultural tradition of art.

Learning Art Anew

Babb had other realizations in Italy. “I pretty much realized I could not draw very well and that if I really wanted to seriously be an artist, I really had to learn how to practice my craft in the same way as if I were a classical musician. I’d be able to read music and play an instrument and really have a deep understanding,” he said.

Although he was a graduate of Princeton, working on a Master of Fine Arts degree at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University in Boston, he had to learn the basics.

“The reason I went to Boston was because the museum school had a reputation for being very strong in that traditional approach to the techniques of painting and drawing,” he said.

When he got there, he realized that wasn’t the case at all. “They had had a revolution, and all of the traditional faculty had left the school and gone somewhere else. And so it was all Bauhaus [artist collectives that created geometric and abstract art] and modernism, and the things that came after at the Boston Museum School,” he said.

There were, however, a few holdovers from the traditional way of teaching art. The museum had a studio where students could copy paintings. And he learned how to grind colors, make gesso and oil paints, and create egg tempera paintings.

But in general, he believes that schools now emphasize innovation: being different and revolutionary. “I do think that in the art schools, we have really missed out. We have not transmitted enough of what is really important about the art of the past to our new students,” he said.

An Apprenticeship With Leonardo

In that early period, Babb felt that he was on his own. Having returned from Italy and having studied art history, something magical happened. “I found myself sort of unconsciously following Leonardo,” he said.

As Babb studied Leonardo’s system of perspective, he found it to be a transformative process: “Because all of a sudden you [could] see vanishing points, and eye levels and transverses, and all this stuff all around you which you would never be aware of if you hadn’t been trained in that.” Then, Leonardo was with him again when he was asked to teach an anatomy course for artists. “I actually went over to Boston University Medical School and

was able to attend the anatomy lab for the dissections and do drawings. … It was just a parallel to what Leonardo would have done back in the late 1400s.

“I remember the first few weeks after I was in there, I started looking at everyone as if they were sort of a complicated machine with hinges and pulleys, and [that] they were operating all this machinery just so completely unconscious of having it, or knowing how. It was very interesting,” he said.

In the 1970s, Babb used to camp on the land where his home and studio now stand in Sumner, Maine. He remembers sitting in the field and doing pen and ink drawings of plants and wildflowers, emulating Leonardo’s style of drawing.

“I realized that all artists are sort of starting from scratch that way, at all times. And of course, it really helps if you have a master who already knows it to learn from, so you’re not creating the whole universe from scratch,” he said.

Between Boston and Sumner, Maine

Two American landscapes dominate Babb’s paintings: the city scenes of Boston and the natural scenic treasures of Maine. Looking back, Babb often wonders why he divided his career between two very different types of landscapes. He went on to say that the city is an environment controlled by linear perspective. Everything is designed by architects, and objects are arranged artificially. Whereas, on the other hand, nature is ordered along completely different lines. It’s sort of self-organizing and disorderly, he said.

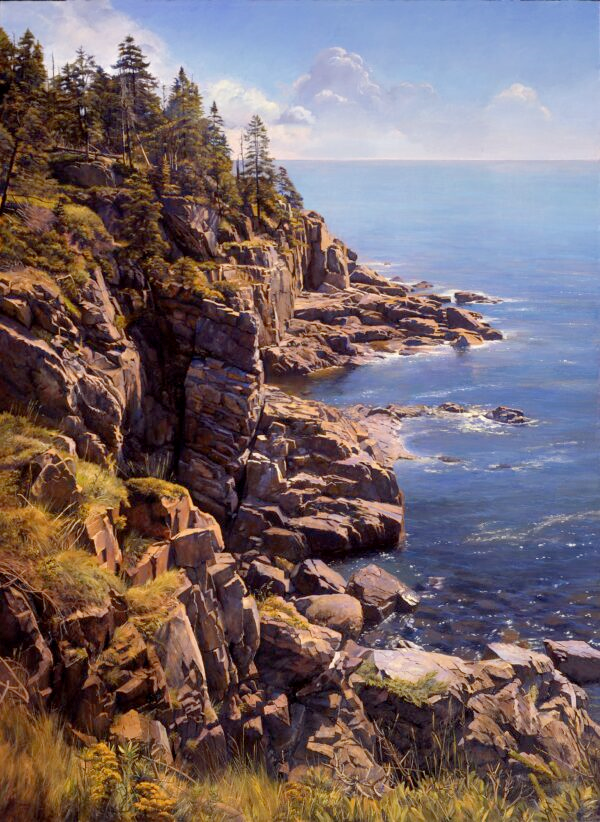

“Mount Desert Cliffs,” 2008, oil on linen; 72 inches by 52 inches. Collection of Janet Starr. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

Boston features in Babb’s painting “Copley Plunge,” which is now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts. Babb entered a competition with two other artists to design a painting for a subway station in Boston. His idea was to create a ceiling painting that would give the illusion of’ the neighborhood above ground.

“Copley Plunge,” 1990, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 82 inches by 65 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

To understand the composition, Babb hired a helicopter and pilot and then flew over the neighborhood surrounding the subway station.

“I became tremendously interested in the aerial perspective of the city,” he said. He mapped out the neighborhoods using an isometric perspective, like the paintings in Japanese and Chinese cityscapes, where objects don’t really have a vanishing point, Babb explained.

“When you’re in a tall building [and looking down], the verticals of the buildings actually do line up at a point that’s directly beneath your feet,” he said. He used this one-point perspective in “Copley Plunge,” where the vanishing point is straight down rather than out on the horizon somewhere, he explained.

Joel Babb’s painting of “Copley Plunge” is placed on the floor to see the effect of the perspective. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

At one time, Babb was creating photo-realistic paintings, in other words, paintings that appear to be photographs. The light spreads evenly over those compositions, he said.

His painting “The Hounds of Spring” is one example of photo-realism. It shows a different perspective from “Copley Plunge.” Babb wanted to create a doorway effect so that viewers feel as though they can almost step into the painting. In the foreground, the plants and rocks are life-size and highly realistic. Babb explained that as you proceed into the painting, up the hill, “the space of the picture will be like transitioning from a microcosm into a macrocosm.” The painting is one of a series of contemporary photo-realist paintings he created.

“The Hounds of Spring,” 1988, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 96 inches by 68 inches. Collection of Harvard Business School. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

But photo-realistic painting is in Babb’s past: “I don’t aspire to be a photo-realistic painter. I want my paintings to look like paintings. I want to see brushstrokes, and I want to interpret the color in a more traditional way.”

Babb’s realist art adheres to the ideals of 19th-century art critic and patron John Ruskin. For Babb, this means, “You should study nature with great humility and not try to impose your own ideas of what it should be on it, but try to learn from it.”

“In a nutshell, the philosophy of realism is that if you really look and explore a very small corner of the universe, you can perceive immense natural forces and universal principles that apply everywhere. I’m not quite sure how the alchemy of that works, but that’s the aspiration,” Babb said.

“Crystalline, The Big Cypress Preserve, Florida,” 2004, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 40.5 inches by 48 inches. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

Past realist painters have helped with that aspiration. “When I think about my own struggle with trying to represent nature, I didn’t get very far until I discovered the drawings of [French painter] Claude Lorrain and the way that he structured the space and the composition.”

Lorrain’s drawings showed Babb “how to structure recession in a natural landscape, overlapping foreground, middle ground, [and] far distance, [and by] alternating light and dark masses, and atmospheric perspective.”

“That traditional way of representing space enabled artists to really represent nature much better,” he said.

A Heartfelt Painting

Most of Babb’s artworks are landscape paintings. He has, however, painted a series of historical medical paintings. The reason is literally close to his heart. At 13 years old, Babb had heart surgery. “It was sort of a live or die proposition, and it was very traumatic,” he said. So in the 1990s, when Babb got a call from a doctor who wanted him to paint the first successful organ transplant, carried out at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in 1954, it piqued his interest.

He’d always been fascinated by history paintings. “Here it was, a historical event with the possibility of doing a significant painting … and so it just appealed to me in all sorts of ways,” he said.

The room where the surgery took place no longer exists, so Babb worked from two black-and-white photographs that were taken during the surgery. He also attended surgeries to become familiar with the operating room setup. Dr. Joseph Murray, who carried out the world’s first successful kidney transplant and who received the Nobel Prize for his work, showed Babb around the hospital.

“The First Successful Organ Transplantation in Man,” 1995–1996, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen; 70 inches by 88 inches. The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

The painting now hangs prominently in The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, opposite “The First Operation With Ether,” painted by 19th-century American portraitist Robert C. Hinckley. That painting details the first use of anesthesia surgery, which occurred at Massachusetts General Hospital on Oct. 16, 1846.

The doctors who commissioned Babb’s painting said to him that Hinckley depicted “the most important surgical innovation of the 19th century, and our operation, in all modesty, was the most important surgical innovation of the 20th century.”

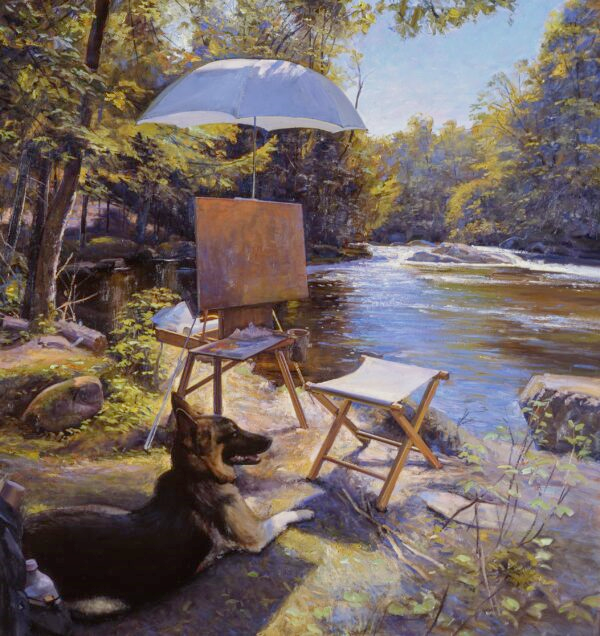

Western Art Heritage Babb believes that a successful painting is the result of a combination of artistic processes coming together. He suggests that artists spend a third of their time painting outdoors and maybe a third of their time painting from photographs, and then the remaining third of their time painting from just their imagination.

“Painting by the Brook, Breughel Watching,” 2012, by Joel Babb. Oil on linen,; 48 inches by 42 inches. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

“I love painting outside. And I think it’s a necessary antidote to using photographs and working in the studio because [in photographs] you don’t see color the way the eye really sees it in strong light until you work outside,” he said.

Realist artist Joel Babb and his dog Ruskin in the woods. (Courtesy of Joel Babb)

Reflecting on his journey as an artist so far, Babb experienced modernism’s sway and the drive to be innovative early on in his school study. But as he moved into realist art, he experienced a sheer reverence for nature and also for the great traditions of the past, about which he’s adamant we shouldn’t ignore.

To find out more about realist painter Joel Babb’s paintings, visit JoelBabb.com

American Artist

March 2004

Maine artist Joel Babb incorporates on-site sketches and numerous photographic references to create scenes inspired by the masterpieces of such artists as J.M.W. Turner, Claude Lorraine, and Nicolas Poussin.

In keeping with its storied artistic tradition, the state of Maine continues to attract talented artists, both year-round and summer residents. In addition to Andrew and Jamie Wyeth, the Pine Tree State also boasts such prominent contemporary painters as Yvonne Jacquette, Alex Katz, Kenneth Noland, and Neil Welliver. Among the up-and-coming artists is full-time resident Joel Babb, whose academic training and study of painters of the past, fueled by a lively intellectual curiosity, have given him sufficient knowledge and skills to make choices of subjects and styles.

Although a number of accomplished portraits and still lifes make up his oeuvre, Babb, an oil painter, specializes in colorful, precise, superbly composed cityscapes—primarily of Boston from the air—and increasingly, local forest, river, and coastal scenes. His work shows the influence of various European and American artists, to whom he readily acknowledges his debt. Most notably, he says early on he felt “completely at odds with avant-gardism everywhere,” concluding that he wanted to apply the language of the Baroque landscape to the contemporary world. A disciplined craftsman, he uses drawings, oil sketches, and photographs in adapting Old Master sensibilities to neo-realist canvases.

Raised in the Midwest, where his father was an Agriculture Department official, Babb attended Princeton, hoping for a career as an artist. In college he studied studio painting with George Segal, but his greatest impression came from a course in Chinese art, taught by Wen Fong. “Long ago I gave up the idea of any direct imitation of the Chinese landscape tradition,” he says, “but I think the subjects and feeling of the paintings I am doing now have something of the feel for nature that I see in Chinese painting, but they are visualized in terms of the Western landscape tradition.”

A brief fling with abstraction ended during a year in Munich and Rome, where he soaked up classical traditions. Babb was particularly attracted to the work of Claude Lorraine, especially his landscape drawings, and Nicolas Poussin. He also cites John Ruskin’s Modern Painters and the Pre-Raphaelites as important influences.

After earning an M.F.A. in painting at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1974, Babb stayed on as a full-time and now a one-day-a-week instructor in realist painting. He became familiar with the museum’s vast collection of paintings, many of which he copied.

While in Boston, Babb began creating sizable, street-level views of historic districts and then big canvases of the city from an aerial perspective. “I got the idea of painting Boston cityscapes in an 18th-century topographical style as if Thomas Girtin or Turner were visiting,” he says. “Later, the great Canaletto exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art encouraged me to try for greater scale and realism in a series of large cityscapes.” To create these works, Babb hovered over Boston in a helicopter with an open door, taking photographs. Later, he used the photos as basis of several sketches.

Babb’s process for developing these works relies heavily on photographs. Preferring to work with many pictures rather than one or two, he says, “I don’t like the composition to be defined by the limits of a camera viewfinder, but by an intuition of the total spatial environment of the place.” For New England Towers, for example, he shot numerous 35-mm slides, several rolls of medium-format film, and a dozen 4″-x-5″ transparencies from the rooftop of a tall building.

Back in the studio, Babb selects the slides he wants to work from and projects them individually on a screen. Using a proportional divider (a drafting device resembling a compass), he measures different sections of various photographs and merges the elements into a consistent perspective, working on a drafting table with a T-square to create the large graphite drawing. Describing some of the challenges of this preliminary phase, the artist says, “The problem with a wide panorama is that long straight lines must be treated as curves, but not appear to be curves. For aerials, or vertiginous views, the verticals have to be straightened or unified in one perspective.”

Babb uses sepia washes of watercolor to establish the value structure, making adjustments as aesthetically necessary. For New England Towers, for instance, he added clouds to the sky and shadows in the middle distance and near tower to make the space more dramatic. Using carbon paper and graphite to transfer the drawing to a smooth canvas, Babb fixes the lines and lays in an underpainting in transparent brown oil paint, using Indian yellow, brown madder alizarin, or umber. He then develops the painting with his palette of oil paints, favoring Winsor & Newton, Old Holland, and Gamblin. His medium is Gamblin Galkyd.

In the studio, Babb uses an oval palette, on which he arranges the unmixed colors, placing the tints about an inch from outer edge, and the shades in the center. “I find this arrangement is very helpful in developing shadows with broken color and creating color harmony,” the artist notes. He uses a variety of bristle and sable flats, as well as a number of palette knives. To ensure correct perspective lines as he paints, he uses a mahlstick and two wooden T-squares along the top edge of the painting, one of which has a nail that can be placed at the vanishing point. “I can run my brush along the edge of the mahlstick or the T-squares to make straight strokes,” the artist continues. “I got the idea from the Canaletto exhibition, where I thought he must have been using something to make his lines so terribly straight.”

Babb’s on-site sketches are vital to the development of his paintings. “They contain the ideas,” he says. “If I go out and take photos without sketching, it’s impossible to tell what was interesting about the spot. I’m at loss for an idea.” He thinks of the photos, in fact, as support material for his sketches. He refers to the sketches, which are 10″-x-15″ or 15″-x-24″ oils on panel, throughout the process. “I need the sketches to figure out the light,” he says. “The more I work from photographs, the more I also work en plein air to maintain a painterly sense of light and freshness of brushwork.”

Babb bases his landscapes on the extensive woodlands, often bisected by brooks and rivers, that surround his home in rural Sumner, Maine. Rather than strictly applying the European landscape approach to his compositions, which would have meant creating idealized views, he determined early on to depict the untamed, asymmetrical reality of forest interiors. “In the works of the Old Masters,” he observes, “one encounters landscapes that are ordered in the way that English gardens are ordered—in strong contrast to the Maine woods.” Babb clearly revels in what he calls “the chaos you encounter” in tramping in Maine’s forests and seeks to transmit that ambience in his paintings.

In evolving his approach, Babb cites two paintings that have deeply influenced him: a large—about 4′ x 7′ work by Gustave Dore, Harvesters Repast, which is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and a smaller oil by William Trost Richards, In the Woods, in the collection of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine. The Dore, he explains, of “an illusionistic scale, in which one could imagine stepping into the foreground and walking into the picture.”

His admiration for the vivid colors and exquisite details of the American Pre-Raphaelites, such as Richards, is reflected in the rosy, romantic light and timeless feel for nature that infuse his forest paintings. In this regard he adheres to Ruskin’s admonition to observe nature faithfully and convey in precise, accurate renderings the light and true colors one has seen firsthand. The result is work that captures the fractured light, dense vegetation, overgrown clutter, and anonymity of Maine woodland interiors, as seen in Sonnets to Orpheus.

Babb’s woodland scenes evolve from numerous preliminary oil sketches made on-site, along with slide views, which are then assembled to define his final composition, just as he approaches the cityscapes. Also like the cityscapes, the artist begins with a brown-yellow underpainting and then overpaints in oil. He works slowly, sometimes taking two months to complete a major work. The artist uses a similar approach in depicting brooks and streams coursing through wooded settings. Featuring tangled woods, jumbled rocks, and serpentine stream beds, they convey a sense of animation and wild beauty.

Much more wide open are his renderings of the pine-clad, craggy coastline of Maine. In Eggemoggin Reach , precisely delineated trees surmount weathered rocks that contrast with the blue ocean water. In preparing this coastal landscape, Babb used several drawings and watercolors, plus photographs taken over a week at the site. In this case he made a preliminary oil sketch in the studio, using “the sky one day, the tide observed on another, and the light on trees from another,” he says. The success of this painting seems likely to prompt Babb to execute more coastal views in the future.

It will be interesting to see in what directions the work of this perceptive and disciplined artist goes in the future. For the time being, he seems content to continue applying traditional techniques, augmented with modern technological aids, to convey the chaotic, sylvan reality of the world around him.

Stephen May is an independent art historian and writer who divides his time between Washington, DC, and midcoast Maine.

Article copyrighted by VNU,Inc.

Over the past dozen years, I have watched Joel Babb paint the Maine landscape. On several occasions, it was my good fortune to see him paint in situ, making small oil sketches with remarkable immediacy. In other instances, on numerous trips to his studio, I observed his large landscapes of woodland interiors in progress, watching how they transformed from monochromatic underpaintings to final, richly glazed works of art.

As the large paintings began to accumulate, an exhibition became imperative. Only vigilant collectors knew Joel Babb’s Maine landscapes, which were otherwise unknown to larger audiences. An exhibition, in fact, would be an exciting discovery for many people. Fortunately, this idea revealed itself simultaneously to others, and I am grateful to Bates College’s Professor Carl Straub, who formally proposed it for Bates College Museum of Art.

-Genetta McLean Damariscotta, Maine August 2002

INTIMATE Wilderness , MAINE LANDSCAPES BY JOEL BABB

Essay by James H.S. MCGREGOR

Joel Babb, who is best known for his minutely observed urban landscapes, turns here to the rivers, the coastline and the woodlots of Maine. The artist, who has long used photographs in his cityscapes, has taken the camera out of its technological and architectural home ground and set it down in the woods. There its omnivorous eye becomes the first element in paintings that elide realistic detail with painterly lyricism and subtle impressionistic effects. Through their bold harmonizing of disparate styles, Babb’s paintings of Maine draw the viewer’s eye and understanding into a widening ring of concentric visions of nature.

Though Babb describes Maine “as the landscape of his heart and soul,” it is not his native place. Born in Georgia, he spent his childhood in the Midwest. From Nebraska he went to Princeton where he majored in art history and studio art. In the studio his teachers were the abstract painter George Ortman and the celebrated sculptor, George Segal. Though Babb sketched from life, he considered himself an abstract artist as the rest of his contemporaries did. After Princeton he traveled to Munich and then to Rome. A sensibility freshly sharpened on Rubens and the meticulous painters of the North traveled south to the hazy, sun‑drenched, ochre tinted scenery of Italy. Once there Babb supported himself by washing dishes in a pilgrim hostel run by Bavarian nuns. Sketching, looking at landscape and at landscape paintings, he became aware of an awakening ambition to paint in the centuries old tradition that his contemporaries seemed set to obliterate. Quite boldly, Babb decided he wanted to paint in the great tradition of Poussin and Claude Lorraine, but to do that he needed to learn their techniques. Growing up he had admired the dedication of two of his sisters‑both classical musicians‑who studied theory and spent hours mastering the technical intricacies of their instruments. Babb began to imagine painting as an art to be mastered by a similar discipline. “The truth about classical music was that one really had to master the past to prove oneself a competent artist in the present.(JB)” Babb returned to the United States to enroll in the Boston Museum School. Like most American institutions, it had abandoned its traditional art curriculum but still offered the study and copy of masterpieces of a great collection. Babb spent hours painting in the galleries in the MFA, where he eventually found a job as a night watchman. After years of work and study, he began to win commissions for urban landscapes.

“I got the idea of painting Boston cityscapes in an eighteenth century topographical style as if Thomas Girtin or early Turner were visiting Boston. I worked outside on location in watercolor and oil. I always made a point of showing the familiar in a new aspect with experimental perspectives; and of course at that point I began to use photography as part of the process.(JB)”

Some of these generally large paintings show the city from street level, others from the prospect of its highest buildings; the most innovative are aerial views based on photographs shot from the open door of a helicopter. All are in prominent corporate and private collections. While he was earning recognition as an urban painter, Babb was discovering Maine on escapes that grew longer and more frequent. In time he became a full‑time resident. The newly discovered landscape of Western Maine became a spur to a new kind of painting. But it also created a dilemma. Babb could easily have applied the techniques he had learned from the masters of the European landscape tradition to represent Maine as they would have seen it. But to do so would have meant sacrificing the vision that made his urban paintings unique. Instead he chose to do something more true to his own vision and more in keeping with the sensibilities of our post‑modern age. Continuing to embrace traditional painting techniques, Babb rejected the idealized landscape those techniques had sustained. He conceived an approach to painting nature that relied on the sketches and photos he made and continues to make for his urban paintings. With these techniques he developed a new way of representing landscape that is pragmatically rather than historically or aesthetically based.

“In the works of the old masters one encounters landscapes which are ordered in the way that English gardens are ordered ‑in strong contrast to the Maine woods. The classical style eliminates spatial obscurity, ambiguity and paradox. (JB)”

Babb does not prune the woods and channel the rivers as the Old Masters did to create an artificial harmony suited to the canvas. Instead his paintings bring nature to us in a form that makes us sec in the gallery not just what but as we see in the woods. In these extraordinary works nature has entered a dialogue with human vision.

A hiker pauses to look at the trail underfoot, then lifts her eyes to trace its course through the trees; finally she considers the slice of sky and cloud above the treetops before walking on. All of these glances fuse in the hiker’s mind to make up the never quite visible reality we call ‘the woods.’ We have only been recreational hikers for a few hundred years. Our remotest ancestors, however, both animal and human, while foraging in these same woods explored its space in the very same way. They worked the ground carefully, stone by stone, stick by stick hunting for food. A rock or a bush attracted them and momentarily held their glance, which then passed on to a split stick, a curled leaf, a hole. Foragers didn’t keep their eyes turned to the ground all the time. Every so often they looked up to take in the wider circle of the woods. Something might be approaching from behind that thin screen of trees; there might be better foraging somewhere over there. Occasionally they looked to the sky, to gauge the weather or the passage of the sun. Out of the millennial repetition of these shifting gazes fixed on three distinct horizons, our optical system of eye and mind evolved a single harmonious and functional view.

While the eye’s mind performs this operation naturally, the painter must find a way of knitting the distinct spaces of the woods together seamlessly and coherently. He must reproduce in two dimensions an optical experience grounded in three. The traditional techniques of representational art evolved to do just that. “Good composition eliminates spatial ambiguities and paradoxes, structuring cues which enable a viewer to build a mental conception of space. (JB)” These classic techniques are a kind of magic that becomes less noticeable and more persuasive in direct proportion to the painter’s skill and training. Executed with sufficient craft, they enable the painter to simulate the optics of true space.

The Hounds of Spring, which is the earliest painting in the show, illustrates both the pragmatic optics and the artistic sleight of hand that makes it visible in two dimensions. On the vast canvas, sparse weeds pierce a dry streambed littered with sticks and withered leaves. The abundant light of early spring glares on the stones and washes out the green of the new growth. A tongue of jumbled rock leads upslope where a screen of saplings and spindly second growth abruptly cuts it off. Above, in the distance, a hazy stand of taller trees merge with the sky. Given the scale of the picture‑eight feet tall and six wide‑it seems an easy matter to step across the bottom frame and walk directly into the scene. The stones, the leaf‑litter and the sparse new growth there at your feet are nearly life size. Every detail is clear: the veining of each curled or broken leaf; the lichen‑mottled surface and water‑shaped edges of every stone; the splintered sticks and sparse stubble of weeds are individual, distinct, absolute.

As you raise your eyes to the painting’s midpoint, just where the rocks disappear into that screen of scrubby trees, the scene changes. Like a musical composition, it modulates from one key to another, from one sense of space and one kind of vision to another. While this is the biological way of seeing in the woods, replicating that way of seeing in a two‑dimensional painting requires the use of expert craft. The appearance of distance must be created by artifice and the biological feel of lifting your eyes to the middle distance must be simulated by technical sleight of hand. Those trees are not so tangible and finely detailed as the foreground objects. The painter has pushed them back by softening their contours and blunting their detail.

As your eyes rise to this sapling hedge, the foreground comes to an end and gains a frame, and in relation to that frame your sense of the space begins to change. It is still the same foreground, of course, but you are no longer seeing it as an isolated peninsula thrusting out of the picture like a chaotic still‑life of cut‑off sprigs and autonomous rocks. Framed by the saplings, it blends into a larger harmony and you experience it differently. Its chaos of individual objects resolves into a larger order. Techniques of composition here simulate the effects of your widening field of vision. The slight diagonal recession of the line of saplings compresses the foreground into a shallow arc which begins at the lower right, swings steeply left, then curls part way back before it merges with the trees. The stones follow this curve; the slight break in the ground near the picture’s bottom edge reinforces it. The broken branches and the bent leafy sprigs align with it like iron‑filings in a magnetic field. The scattered green leaves of the foreground begin to resonate in harmony with the denser green beyond.

No sooner is this second vision gained, than your eye continues its journey up the picture. Abruptly this second sense of order gives way to another. The hiker and forager don’t often look this far; the two lower horizons are the most important and productive. Up there the woods seem insubstantial, there are only suggestions of leaf and branch. Foliage becomes an insubstantial fog as soft and transparent as the nearby masses of cloud. Looking back on the whole picture you can repeat the itinerary from top to bottom, or reverse it. You can choose to move from distinct foreground objects, through an organized field of objects to a range where objects dissolve into phenomena of light and color. If your eye moves in the opposite direction, you pass from a filmy and suggestive range of light to a stark and autonomous reality. This itinerary, through the painting’s three concentric regions, has many meanings for the artist. Based on a natural kind of seeing, it also represents his concept of what the woods‑experienced directly or re‑experienced in paintings‑can do to awaken our souls and our sensibilities. For all its realism and biological optics, this painting began in a visionary experience:

“On an evening walk the idea for a great painting came to me suddenly: tiers of stone and weeds burnished golden by the high summer sun, late afternoon, pink thunderclouds threaten‑ing a consummation of the day. Small plants and weeds in the foreground make up a vast architecture for the oblivious industry of insects. All are to be painted life‑size, illusionistically, so that the observer will feel that he can walk into the picture. This stuck in my mind at the time, that one could observe an essentially overlooked corner of the universe, and if it were rightly observed one could see the play of powerful universal forces‑at a small scale, but the same forces as at vaster scales. The rocky path which rises is a kind of ladder and above it forested slopes, above that the towers of clouds: a great, full allegory of fate, nature, and the being in which the soul is entangled. (JB)”

A traditional landscape painter would have returned to his studio and set about recreating his vision through imagination. Babb intended to create his painting with the same fidelity and using the same approach he had perfected as a painter of cityscapes. This required an exploration of the space through sketching and photographing. But when he returned to the landscape that had inspired him he found that his vision had faded. A year later he was exploring the paths ascending Tumbledown Dick.

“On the lower trail I find perhaps the background for my picture: remote trees fringing the edge of the mountain framed by nearby forest, shimmering grass and green foliage ascending in ranks to the bottom of the cliffs. Further up the trail has been washed away leaving a rocky backbone. Perhaps this is the basis for the foreground. Cutting away maple boughs that encroach too much on the light, I set the big camera, studying the field on the ground glass. The light has become hazy, shadows soft; the space enclosed by the crowding vegetation makes the washout feel cozy and self‑contained. This is Spring. The detritus of last year’s leaves, preserved, skeletal, cadaver‑like, covers the rocky terrain‑woodiness bleached, but the pale green of new growth everywhere fresh against the gray and brown, refracting light in exuberance from the secret heart of things (JB).”

In this indirect way the essential form of the original vision and its secret meaning came to life. Babb called his painting The Hounds of Spring recollecting a line from a Swinburne poem that celebrates the animal power of the awakening season.

The Origin of Wilkinson’s Brook has the same three part structure as Hounds and reflects the same way of seeing in the woods. But because it is a smaller picture and its elements are more subtly blended, this similarity is disguised. In the foreground last year’s withered leaves are pierced with the green of new shoots, ferns and mosses. A long scar splits the bark of a lone yellow birch tree. Following the curving stream from the front left, the eye is drawn up and to the right into the obscurity where the brook perhaps begins or where it merely bends out of sight. From that dark place two streams of light lead upslope through a haze of trees toward a morning or twilight sky tinged orange. Though the path is very different, the itinerary within the picture from the substantial to the ethereal is familiar. On maps the brook is unnamed, but Babb has named both it and the painting in honor of George Wilkinson, a friend and mentor and the man who introduced him to Maine.

“George and his wife Mary, who had two grown daughters, made a habit of befriending lost young people‑and I certainly qualified as that. The first time I set foot on the land, George had driven me up and showed me around the property, including the brook in the painting which is the back border of the land. I camped under a sheet of plastic and he picked me up a week later. In subsequent years, I would take the bus to Lewiston, then a local bus to Peru, then hike the 7 miles to the land for a week or so. George soon said he would title me over an acre if I would build a house. (JB)” The house, where Babb and his wife now live year round, was completed in 1984.

If you could somehow step back from the tumbling stones clogging Gooseye Brook, this picture would resolve itself into a Currier and Ives scenic. But Babb has let loose an avalanche of rock against their conventional point of view. Rock all but replaces the water and redefines the brook as a Zen master’s river of stone. From this low vantage point a fly‑fisherman would plot a silent approach to the stream. A child would know that the rocks were meant for scrambling up; that they are what is really interesting about this part of the brook. All those water‑rounded, lichenous stones, roughly similar but all distinct, randomly scattered but also subtly wedged by the current of spring floods, show on a modest scale how nature does her work. Above the rocks a little of the brook appears and bends them in an arc; further up the autumn leaves dissolve in a golden haze. The great whale of rock that blocks the channel of Big Niagara becomes, when you can tear your eyes away from it, a main thrust in the river’s serpentine sweep through space.

In Eggemoggin Reach (pg. 16), there is more room to breathe and more air to take in. But despite appearances the painter’s magic is repeated here over and over. The implacable rock of the headland, so alive with color and so diverse, dissolves to a monochrome in the distance. In the left foreground it merges with the shapeless seaweed that floats on the transparent tide like Monet’s water lilies. The inlet behind is nothing but a glaze of color. The domineering pines lead up to one at the painting’s center that seems about to dissolve in the brilliant sky. There are no human figures in this painting or any others in the show. But they are not lonely. We are in them. They are nature reproduced in those loving contours that our eyes give her. They are domesticated by the harmony that resonates between transcendence and particularity; they are the very story that our way of seeing tells.

Shakespeare’s Prospero saw that art and the world it represented could…

melt into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud‑capp ‘d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded

Leave not a rack behind. (Tempest, act 4, verse 151‑156).

Shakespeare’s vision rested on theological and metaphysical foundations that for good or ill have eroded steadily as the modem era has progressed. Babb believes that a vision like his stands on something deeper within us that can be ignored but not undone‑the biology of the human eye and the organization of the brain that deliver a world to us. His paintings prove that despite appearances‑indeed because of them‑the realist can still be a lyricist: in human eyes the rocks are intimately linked to the clouds.

Down East

March 2002

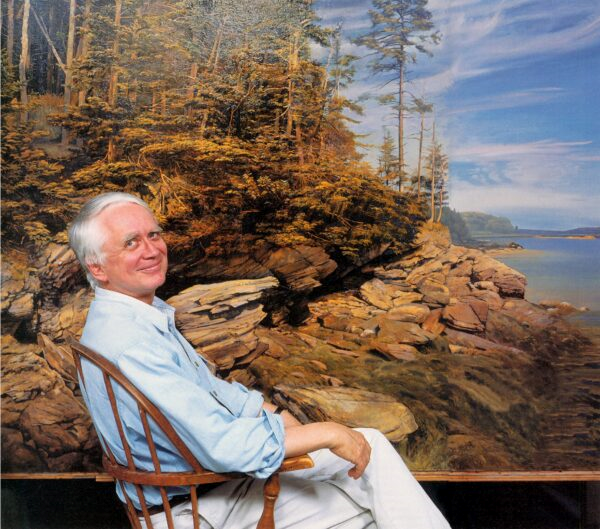

Despite having lived and worked in Maine off and on for thirty years, Joel Babb remains an elusive figure in the Maine art world. A precision realist whose paintings of the Boston skyline and the western Maine woods rival the urban virtuosity of Richard Estes and the environmental sensitivity of Neil Welliver, Babb is too good to go entirely unnoticed, yet he somehow has never fully registered as a major Maine artist. Tracking him down at his home in Sumner suggests several reasons why this might be.

“Up here I’m a Boston artist. Down there I’m a Maine artist,” says Babb, putting the matter most succinctly.

Joel Babb is a gracious man with a casual yet cultured manner about him. His neatly combed white hair and glasses give him a studious, professorial air that seems slightly misplaced out in the gravel hills and woodlands north of Buckfield. Babb’s modest gray board and batten home and studio are like an oasis of urbanity in the boondocks, a private space filled with books and paintings, classical music and the aroma of cranberry muffins freshly baked. As Babb settles in at the kitchen table to talk about his unusual career path, his wife Frannie works silently at the computer, and his German shepherd Ruskin noses the stranger at the table.

Joel Babb was born in Waycross, Georgia, in 1947, but he grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska, where his father worked for the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Growing up in the heartland, he might have been expected to seek out a career in science or technology, but Babb says he was always inclined toward the arts.

“My mother’s father painted a bit, I had an uncle who was the art director of TWA, and one of my cousins was an artist who studied at Cranbrook (Educational Community, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan),” says Babb, “so I thought of art as being a potential career.”

Both of Babb’s sisters—one who is now a cellist and director of the strings program at Washington University in St. Louis—were gifted musically, and Joel’s artistic talent surfaced early on.

“My father,” he quips, “can’t understand what happened to his family.”

At Princeton, where his freshman roommate was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s grandson, Babb earned a degree in art history in 1969 and then set off for Europe where he ended up washing dishes for an order of German nuns and “absorbed the classical tradition in Rome.”

In 1971, Babb got into Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts based on the recommendation of George Segal, the realist sculptor renowned for his white plaster figures and one of Babb’s Princeton professors. Though Babb had come to Princeton as a budding abstract painter, his art history studies inclined him toward the Baroque, and his time in Rome left him with an appreciation for the Old Masters. In Boston, studying at an art school affiliated with the Museum of Fine Arts, he says, “I found the museum’s collection to be the best place to learn.”

Babb earned his MFA in 1974, bet he never really left the Museum of Fine Arts. From 1974 until 1986, he taught painting and drawing through the museum’s education department, and, since 1986, he has taught a painting course at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Each Friday, he drives to Boston from East Sumner, a hamlet northwest of Lewiston-Auburn, to teach a Saturday class in realist painting.

Babb first came to Sumner in 1971. Working as a museum guard while attending art school, he met a fellow guard who had recently purchased a dilapidated old farmstead out on the Greenwood Road for $2,000. Invited to Maine for a visit, Babb fell in love with the place and, four years later, his friend sold him an acre of land for a dollar. The tidy little warren of rooms he now inhabits began with a one-room cabin he built for $1,400. Subsequently, Babb added a studio and, when the Museum of Fine Arts had no use for a workshop building it had erected in it’s courtyard to house a visiting Japanese sword maker, Babb took it apart and reassembled it in Sumner.

When Babb married in 1980, he and Frannie, who worked as a book buyer in the museum shop, began splitting their time between a home in Hull, Massachusetts, and the cabin in Maine. Fifteen years ago, however, they sold the house in Hull and moved permanently to Sumner where they live very simply—wood heat, no backup, no cable TV, no mortgage.

Living frugally in Maine, says Babb, is what has made it possible for him to concentrate on making art rather than teaching art.

“It’s really been a key to becoming a painter,” he says. “Not having a mortgage allowed me to paint.”

A 1974-75 oil painting that hangs in Babb’s home provides an indication of his early and continuing enterprise as an artist. Entitled Allegory of Creation as a Workshop, the painting depicts a rude workshop filled with all manner of tools. Outside the workshop is a tree covered with scaffolding and rigging, as though the unseen artisan is either trying to build a tree or, at the very least, direct its growth. While his first artistic impulses may have been abstract, Joel Babb’s education and experience have given him a pragmatist’s appreciation for the value of craftsmanship.

“I take the example of classical music as a model,” he says. “Even if you’re and avant-garde composer, you should have an instrument and know how to play.”

Many of Babb’s early paintings were “allegories of work,” didactic paintings of marble quarries in Italy and Bath Iron Works in Maine that spoke to the dignities and dangers of hard physical work. It is a subject he returns to from time to time, as he did in 1995 with Automation, a fantastic painting of a colossal paper machine at the International Paper Company mill in Jay being manned by a sole operator.

“Nobody was interested in the least” says Babb of his early workscapes. “No one had any idea where I was coming from. So I started doing drawings and watercolors outsid around Boston. I was looking at eighteenth-century English watercolors by painters such as Turner and Girtin. I decided I was going to use an eighteenth-century style to paint modern subjects. People began to buy my watercolors of Boston and that launched my topographical career.”

Babb is best known for his incredibly realistic and impossibly detailed aerial views of modern Boston and, to a lesser extent, Providence. Viewed from helicopters and skyscrapers, Babb’s Boston cityscapes reveal a crazy quilt cubism of historic brick blocks and gleaming glass towers, rooftops, and landmarks.

“Being the Canaletto of Boston would be a great thing to be,” says Babb, “when you think about what he did for Venice.”

Babb’s photorealist panoramas of Boston became very popular with top-drawer law firms, financial institutions, hotels, hospitals, and universities in the metropolitan area. They also led to non-cityscape commissions such as the 1995-96 oil Babb painted for the Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard commemorating and called The First Successful Kidney Transplantation.

Along with his geographic remoteness and the city boy/country boy split personality of his work, another factor that has contributed to Joel Babb’s low public profile is the fact that he has tended to work through art consultants and on commissions rather than the more visible gallery and museum route. Though he has been represented at various times in Maine by Hobe Sound Galleries North in Brunswick, J. S. Ames Fine Arts in Belfast (both now defunct), and Frost Gully Gallery in Portland (now removed to Freeport), Babb’s sole representative at the moment is Trudy Labell Fine Art, and art consultant formerly in the Boston area and now based in Naples, Florida.

Art galleries generally work on consignment, paying an artist only when a painting is sold, but Babb says Trudy Labell, who has handled his work for eighteen years, has often purchased paintings outright to enable him to keep working. His paintings currently fetch between $6,000 and $25,000 depending on size.

“Joel is extremely modest. He doesn’t care about the prices, but he has to live,” says Trudy Labell. “It would be easy to take advantage of him.”

Since Labell relocated her business to Florida four years ago, Babb has added paintings of cypress swamps to his repertoire, but, after devoting most of his attention in the 1980s and 1990s to urban landscapes, the focus of his energies more recently has been painting the forests of interior Maine.

“Over time, I’ve identified much more strongly with life up here,” says Babb, “so I’ve gradually extricated myself from the city.”

Babb points to a 1988 painting, The Hounds of Spring, as a breakthrough landscape for him. A rather impressionistic view of an uninspiring subject—a washed-out logging road near Tumbledown Dick Mountain—The Hounds of Spring captures Babb’s sense of being in nature, not just looking at it. It is a painting about the regenerative powers of nature, the forest reclaiming its wildness form the destructive forces of human enterprise. Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, The Hounds of Spring now hangs in Baker Library at Harvard Business School.

Where Babb’s cityscapes have a thoroughly modern, photorealist look to them, his woodland landscapes have a romantic cast to them, a quality of rosy light that seems to lift them out of the here-and-now toward eternity. Babb does not feel, however, that there is a stylistic dichotomy between his urban and rural paintings. Rather, he suggests that his aesthetic interests have evolved away from the objective examination of specific urban sites toward a more imaginative evocation of non-specific natural sites.

All of Babb’s paintings begin with direct observation. He starts by producing small oil studies based both on observation and photographs. In his most recent work he has scanned multiple photographic images of a scene into his computer in order to manipulate them into a photomontage he can use for reference. When he has composed a painting using photographs, he tiles off a canvas into a grid of squares and transfers the composition. Then he executes a complete tonal underpainting in shades of brown and yellow. At this stage in the process, his paintings resemble nature as seen through the yellow lenses of sportsmen’s sunglasses. Finally, he paints over the underpainting in oil, working anywhere from six to eight weeks on each major painting.

Whether Boston from the air or Maine from the ground, the visual interest for the viewer in Babb’s painting is the subject matter, yet the color and forms in the paintings are functions of the artist’s formal concerns with light and perspective. Natural landscapes organize themselves by the overlapping of forms, but cityscapes operate via linear perspective, and Babb is not above playing fast and loose with the geometry of vision.

“The challenge to me in doing a commission is to do it from an unusual perspective,” says Babb. “That’s why I’ve found these commissions more stimulating than stultifying.”

Babb is masterful at manipulating perspective. His paintings may look convincingly realistic, but they often describe a reality the naked eye will never see. He once, for instance, spent months trying to work out how Boston would look if seen from underground, an exercise he undertook in hopes of securing a commission from the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority that operates Boston’s subway system.

While unsuccessful in that underground project, Babb learned enough in the process to paint vertiginous overhead views of the city such as Copley Plunge, a view from the Hancock Tower which has a one-point perspective with the vanishing point going down rather than out toward the horizon. To accomplish this illusion, Babb showed streets as parallel that the eye would see as heading toward intersection.

“I think Joel Babb is one of Maine’s finest painters in his conceptual thinking as well as his ability to execute,” says Genetta McLean, director of the Bates College Museum of Art, in Lewiston.

Later this year, in November and December, the Bates College Museum of Art will feature Joel Babb’s Maine landscapes in what will be his first solo exhibition in Maine since Bates exhibited his landscapes at the old Treat Gallery in 1984. While Babb’s work was included in Green Woods and Crystal Waters organized by the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa in 1999-2000 and in Representing Representation V at the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, in 2001, the Bates show will be a rare opportunity for Maine audiences to see what Joel Babb has been up to lately. And Genetta McLean says that’s something special.

“It’s a realism that reaches back to an Old Masters way of working, but he keeps it up to date by working in the Maine woods,” says McLean. “I’ve visited Joel’s studio often, and I’ve seen that he does everthing with great craft and finesse. That’s not a normal experience.”

The Babb exhibition was suggested by Bates religion and philosophy professor Carl Straub, who intends to use Babb’s visions of the Maine woods as a resource in teaching a course entitled “Nature” in Human Culture.

“I am encouraged that Joel is getting away from the geometrical, architectural murals hea has been so successful with in Boston, and moving in the direction of more free, more lush, rich and fecund portraits of the woods,” says Straub, a summer neighbor of Babb’s in Sumner. “He does seem to be very successful in conveying the depth of nature. Joel is steady, relentless, and unabashed in his eagerness to paint. I think he follows his own stars.”

Medicine in American Art

The First Kidney Transplantation

Stefan Schatzki’

The first human kidney transplantation, one of the seminal events of medical history, occurred on December 23, 1954. After several years of research, including successful kidney transplantations in dogs, the transplantation team at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, MA, was searching for a way to apply their technique to humans. On October 26, 1954, Richard Herrick was admitted to the Brigham with chronic nephritis, and it soon became evident that he was going to die. Richard’s twin brother and best friend, Ronald, agreed to give one of his healthy kidneys to his brother. Extensive testing was carried out, including a successful skin graft from Ronald to Richard and fingerprinting of the brothers at a local police station. The latter test led to a news leak and daily requests for information from the press.

Consultations followed with experienced physicians inside and outside the Brigham, clergy of all denominations, and legal counsel. The transplantation team, led by Joseph E. Murray, a plastic surgeon, and including John Merrill (nephrologist), J. Hartwell Harrison (urologist), and Gustave Dammin (pathologist), as well as a psychiatrist, met several times with the Herrick family. It was only then that the transplantation team was comfortable in offering the option of a transplantation to Richard, Ronald, and, by extension, the Herrick family.

The First Successful Kidney Transplantation, 1996

Oil on canvas, 70×88 inches, Harvard

Richard had reached the final stage of his disease. First, the surgeons wanted to do a test run. They needed an appropriate cadaver on which to do the surgery to be certain the kidney would fit in its new site. On December 20), a cold and snowy day, a suitable subject became available and the test surgery was successful. The Herrick operation was scheduled for 3 days later.

On December 23, with intense media attention, the surgery began in two operating rooms. While Murray prepared the transplant site, Harrison was isolating one of Ronald’s kidneys. At 9:50 A.M., Murray gave Harrison the go‑ahead to sever the blood supply to the donor kidney. Francis D. Moore, chair of the Department of Surgery. carried the severed kidney into the room at 9:53. One hour and twenty‑five minutes later, the vascular anastomoses to Richard’s new kidney were complete. There was a hush in the room as the clamps were removed, followed by grins as the donor kidney turned pink and urine began to flow briskly.

Richard thrived and married his recovery nurse. They had two children. However, Richard died in 1962 from a recurrence of his original kidney disease in the transplanted kidney. Murray received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1990.

This historic surgery opened the immense field of transplantation surgery. The event is memorialized in this painting, which recreates the events of December 23. The painting hangs in the main lobby of the Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard Medical School on a wall directly opposite Hinckley’s famous painting, Ether Day (AJR 1995:165:560).

Joel Babb (1947‑ ) is a graduate of Princeton and the Boston Museum School, where he taught for several years. He has also taught at Tufts and Harvard universities. In discussing his work, Babb states that “the study of art history and the influence of Rome and the classical tradition were the sources of the desire to set aside modernism and ground a study of painting on earlier models” (personal communication). His 1970 landscapes and views of Boston were “based on drawings and developed in a technique related to Baroque landscapes” (personal communication). He is perhaps best known for a series of realistic, topographically accurate cityscapes of Boston, which are in prestigious collections throughout the Boston area In the late 1980s, he began a series of large landscapes of the Maine woods that have recently been exhibited at the Bates College Museum of Art in Lewiston, ME. His paintings have been exhibited in many museums and galleries throughout the Northeast and are in numerous prestigious corporate collections and several museums, including the Fogg Museum of Harvard University.

He has recently completed a portrait, which will also hang in the Countway Library, of the famed cardiologist Paul Zoll. Babb indicates that “the transplant painting was pure excitement and stimulation throughout” and that “the subject itself has a Promethean grandeur that the painting barely reflects” (personal communication).

Joel Babb (1947‑). The First Successful Kidney Transplantation, 1996. Oil on canvas, 70×88 inches, Harvard

-American Journal of Roentgenology, 2003

L I N K S

- “The Canaletto of Boston”, Princeton Alumni Weekly, November 2000

- Bates Museum of Art, Maine

- American Artist Magazine

P U B L I C A T I O N S

- “Green Woods & Crystal Waters: The American landscape Tradition”, Philbrook Museum of Art, March 2000

- “The Artist and the American Landscape”, First Glance Books, June 1998

- “Carried Away: The Joy of Collecting Art in Maine”, Bates College Museum of Art, June 1999

- “Representing Representation V”, Arnot Art Museum, October